Part One

Palace's Corner Problem

Nine games into the season, Crystal Palace have had to defend 48 corners in league fixtures. These corners have resulted in 23 shots on goals. Six of them have found their way past Vicente Guaita and the Palace defence.

In percentage terms, that means Patrick Vieira's side has conceded from 12.5% of the corners they've faced, 23.1% of the times the opposition gets a shot away, either in the first or second phase of defending.

Palace has given up 108 shots in total this season. Once you remove the shots from corner phases and Mikel Alonso's free-kick in the league opener, then Palace, on average, concedes a goal every 0.08 shots. It is 0.13 with set pieces, joint worst in the division with Newcastle and Norwich.

Credit where credit is due, overall, Palace have restricted teams to relatively few shots. They are 7th in the league for the fewest shots, although a much higher percentage find the target than the sturdiest defences.

Those overall shot totals remain skewed by the performances of the team against corners. Newcastle is the most recent example, being the difference between a win and a draw.

Palace's defensive setup on corners hasn't been an apparent weakness over the last four seasons. Hodgson's various lineups conceded 8.5 league goals on average per season.

Multiple Phases

Opta defines a goal conceded "directly" from a corner with quite a narrow lense, as by their statistics, only two goals have been conceded from corners this season.

Those goals, both the aforementioned Callum Wilson goal and Mo Salah at Anfield, ignore the bigger picture. Sadio Mane's rebounded effort for Liverpool wasn't the initial shot but was "direct" from a corner, even if it wasn't the first shot.

Defending corners, therefore, becomes about stopping multiple phases of attack. There is the initial cross to deal with, either directly or from a short pass. Once cleared, the defence needs to shut down a follow-up shot or cross quickly.

Stopping that second phase is about quickly organising and resetting your defensive shape. If the second ball leads to a cross, the team must have already cleared their lines and stepped up as a unit. This increases the chances of catching forwards offside.

If facing a shot from the second ball, the midfielders or shorter players less likely to be in the aerial tussle will have to show the anticipation shown at the other end of the pitch. A team cannot afford passive watchers of the ball. Bodies need to be on the line to block.

Choosing a Scheme

It's overly simplistic to think any team operates a single scheme when defending corners, but they are often categorised into the "traditional" man-to-man and zonal marking.

Old Liverpool central-defenders / former-pundits on MoTD would undoubtedly scoff at the idea of "European" zonal marking, but it has its merits alongside the man-to-man focus.

Most teams use a hybrid system, which in truth, even the older style of man-to-man marking used to an extent having a player on the front and back post. As anyone under 5'9" would have experienced in Sunday League football.

Whether it was Glenn Murray and Marouane Chamakh of old or Christian Benteke, defending the corner of the six-yard box for the low or near-post is a typical example of zonal marking. They have a designated area to protect, regardless of how the opposition is set up. This can be replicated across the six-yard box, as that is the crucial area to defend, and players can move out to attack the balls closer to the penalty spot.

If the attacking team adds a short option or has more players outside of the box, it drags more defenders away from the goal. Settling on more zone setup helps prevent teams from dictating on how to defend.

Ultimately finding the way that suits the players at your disposal is the key.

The Role of the Keeper

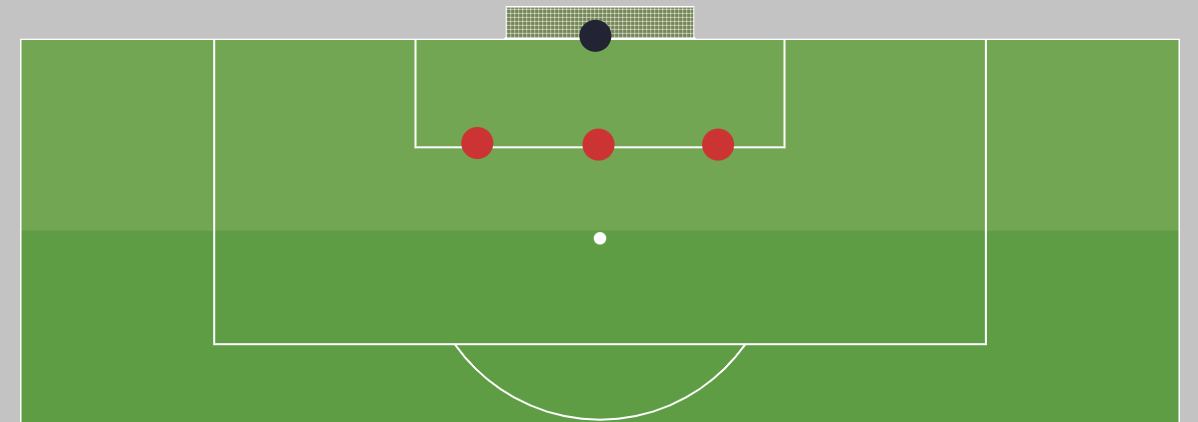

In general, the goalkeeper is set up centrally in the goal, drifting out to deal with the out-swinger and moving towards their line for the in-swinging ball.

Size does matter when it comes to stopping crosses in general, coupled with long arm lengths. It's no surprise when you look at the percentage of crosses stopped by a goalkeeper this season, Robert Sánchez, Illan Meslier, and Alex McCarthy lead the way. The first two are listed at 6'6". Of the top six players, and only David Raya would be considered "undersized" in the Premier League.

Vicente Guaita, in this respect, compared to other 'keepers, isn't naturally as dominant in the air. He is a good shot-stopper and has proven invaluable in that sense at times. But it isn't fair to expect him to come for crosses like Nick Pope does, consistently for Burnley. It would seem that he has to overreach and punch the ball more frequently under Vieira, and there are fewer clean catches in his six-yard box.

Under Roy Hodgson, it appears Guaita was given a "cleaner pocket" to work inside of. Hodgson had the benefit of Gary Cahill or Scott Dann, who were able to remove more of the pressure in this area.

Possible Solutions:

Given what we have seen this season, what areas could help improve Palace's defending of corners?

Remove the Player from the Near Post

Having a player on the near-post is there, in theory, to prevent a goal. Preventing the initial header/shot is arguably more valuable, as even when Palace are winning the first header, it currently isn't always the best clearance.

In the case of Palace's conceded goals this season, the issue hasn't been losing out in the first defence phase, but rather the second. Taking Tyrick Mitchell away from the front post also creates a channel for a striker to be caught offside in the second phase, which is helpful in an era of VAR reviews.

Add More Zonal Marking

At Palace's defensive peak in year's past, the core of the man-markers would have contained Damien Delaney, Scott Dann, and Mile Jedinak. Each was a physical player, experienced, and suited to winning the majority of their aerial battles.

Joel Ward likely wouldn't have been in the top three players to be a man-marker, yet he now finds himself one of the three in more cases, especially when Cheikhou Kouyaté isn't in the side.

By reacting to their designated player, rather than watching the ball's flight, the attacking player already has the advantage in all cases. Coupled with Palace's ball-playing central defenders and Ward, who aren't renowned for being exceptional headers, this becomes a weak spot.

Switching to more of a zone scheme, the likes of Andersen can be designated an area to attack the ball rather than reacting to his man, which may suit him better. Protecting the six-yard line at all costs.

Andersen, in particular, is currently having a down year winning aerial duels in this instance or open play. Whilst it is likely, he will improve back to his usual average. At the moment, he is winning 12% fewer than Gary Cahill did last season. A switch away from tracking a single player could help him.

Focusing on Organisation

Conor Gallagher and James McArthur are exceptional at closing down and turning the ball over higher up the pitch. But this same skill set doesn't appear to be as effective on the edge of Palace's area.

Having a set plan to push out the line of defence requires leadership and organisation, and the players in front of them need to make sure they are first to the second ball. They cannot be passive or ball-watching, as the team needs to focus on defending as a unit.

Moreover, corners should present a chance to counterattack. Having a defined place to clear to each time, much like an "outlet" pass in basketball, Palace can take advantage of the pace of a Zaha or Olise on the break.

Practice makes perfect, so this is about repetition, repetition, repetition. As the pressing game outfield has improved as the team is adjusting to the pressing game, Patrick Vieira can apply the same ethos to this one, which must have happened under Tony Pulis. As a stickler for working on set-pieces, offensively and defensively, Palace had a reputation for being a good set-piece team in his short stay.

Using a Specialist Late in Games

If the Brighton, Arsenal and Newcastle games proved anything, it is that Palace hasn't been tremendous at holding onto their leads. The introduction of James Tomkins was designed to add more defensive capability, but the area became more congested as a result.

While subbing off a central defender may not be a route that managers often go down, Palace's pairing primarily is there to build the possession game to attack, rather than being "stoppers" at the back.

As Palace look to close out more games with a slim lead, utilising James Tomkins and his experience does make sense. A specialist player who deals with long-balls and corners seen at the end of a game could be a cutting edge and avoid disrupting the midfield shape in front of the defence.

Hiring a Specialist Coach

If the current coaching staff cannot fix the issue, then find a coach that can. We have seen teams like Liverpool bring in consultants to work on corners and throw-ins. A hire like this is a worthwhile exercise, especially given the monetary value for each league position.

Alternatively, if this isn't a coach from the "new" generation, looking at part-time senior staff who are used to "old school" football could be another way to get back to defensive fundamentals.

In part two tomorrow, we will look at each goal conceded to break down what went wrong.